Our Weekly Entertainment Dispatch

Perhaps the best spy story ever told. Or… not?

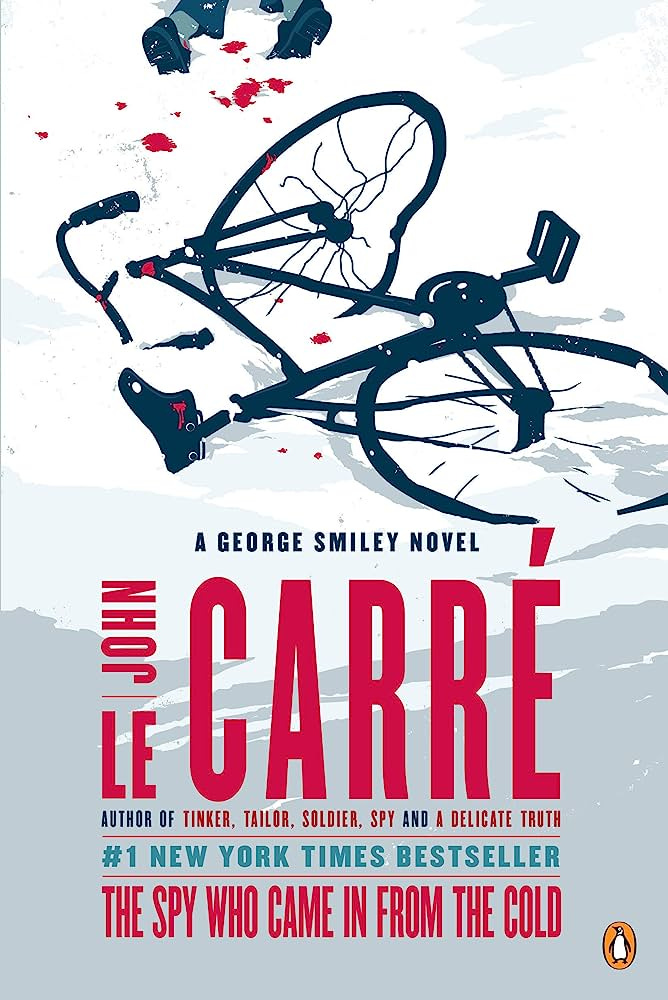

The Spy Who Came In From The Cold

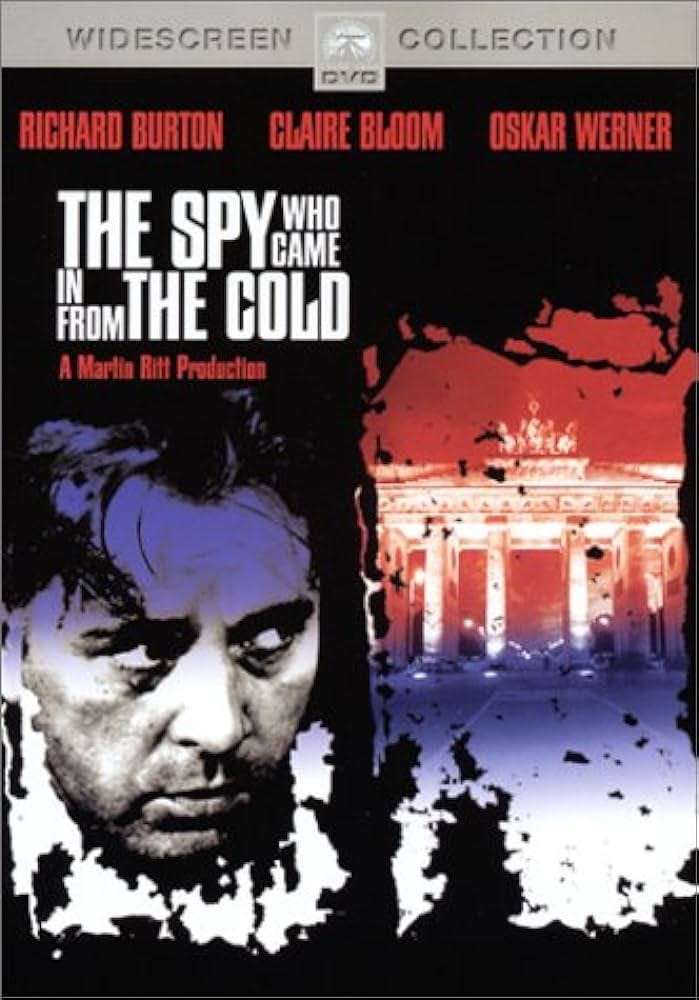

In 1963, John le Carre (real name, the less exotic David Cornwell) published his third novel, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold. It was an instant classic, considered by many the best spy novel of all time. Inevitably, the movies came calling, and in 1965 a British film of the same name, starring the iconic Richard Burton, was released.

So: Do the book and the film live up to their vaunted reputation?

The book surely does. Le Carre was, even then, a master storyteller. The novel unfolds in a series of delicious realizations, and yet we feel less manipulated than involved; there is the sense of living inside an enormously clever mind, one that’s decided to include us in a rarified world.

But what made the book a landmark in the genre is that le Carre clearly knew the work. A former member of England’s domestic intelligence service (MI5 — think, “FBI” without arrest powers) as well as MI6 (think CIA), le Carre’s intelligence agents are anything but glamorous. As in real intelligence work, his characters cover the swath of smart, dedicated, ambitious, maneuvering, petty, venal functionaries one finds in any bureaucracy (especially a government one). (A retired Agency veteran once told me early in my career: “In Langley, we run our best operations on each other.” I never forgot that).

Le Carre also clearly knew how intel operations work, how very often the people conducting them don’t see the whole picture until later (if ever), and that, as we used to say at work, “the enemy gets a vote.” In short: despite all strategizing and intriguing, little ever goes according to one’s plans. Or the plans of whoever is pulling the strings above you.

The book remains captivating, and is soaked in small details of Cold War Britain that give it great authenticity (did people really eat something called “calf’s foot jelly” when sick?).

So then: What of the movie?

Wisely, the screenwriters didn’t attempt to capture all the nuances of the novel, letting the plot and acting carry the show. It works. Much of the credit goes to Richard Burton as the main character, whose craggy, weathered face and haunted eyes convey the existential dread of an intelligence officer approaching the end of his usefulness… and perhaps the end of faith in his life’s work.

His opponents, Soviet East Germans, are appropriately brittle martinets — nobody believed like a Cold War communist — and the black-and-white the director chose adds the proper austere atmosphere. One feels that Burton is truly “out in the cold” — in every sense.

So why am I hedging?

Simply this: The movie has a flaw. In my mind, one fatal to the story’s plausibility. And having just re-watched the film, I have assured myself — it is there.

What would it be? Not telling! Let’s just say there is an assumption in the planning and execution of the (ostensibly) brilliant intel op the story centers on that renders it pretty much impossible to have been planned and executed as portrayed. (Tellingly, this flaw is explicitly not there in the book).

But let’s be clear: the film is still first-rate, a classic of the genre, and well worth watching. And the shock of the ending loses none of its revelatory power.

So: A free OpsDesk paid year-long subscription to any reader who spots this inconsistency (or proves me wrong!). We’ll give the reveal next week.

The movie is available on Amazon Prime, as well as the free library app we’ve often referenced, Kanopy.

And here’s the book (a whole two bucks on the Kindle app).

Both are well-worth your time (the book is, as ever, the deeper experience).

In the meantime: All of us hope you had a great Thanksgiving! We’re all still here, and that’s a lot. (And as another writer recently pointed out in this excellent short piece: We all have a lot to be thankful for).

So: Stay safe!

Not so easy, these days.

Enjoy the movie and support your local police!